The article “Where Have The Good Men Gone?” in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal follows up on the New York Times article “What is it About 20-Somethings” with the perspective that perhaps men are extending adolescence longer than women…causing a dating conundrum amongst 20-something women. This may not be limited to 20-somethings. I recently met an amazing 60-something woman — accomplished, beautiful and charming. She mentioned that dating in NYC is difficult. Her advice: “A dog is a great way to save you from dating jerks. When you are on a date and realize you would rather be walking your dog you know it’s time to go.” There is an old stereotype that men are dogs…apparently not even. But perhaps we just need to to create man years like dog years. If a dog has 7 years for every human year, maybe in accordance with these article, man years would be age divided by 7. Just a thought. What would your equation be?

Where Have The Good Men Gone?

Kay S. Hymowitz argues that too many men in their 20s are living in a new kind of extended adolescence.

![[Review cover]](https://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AB753_Review_G_20110218215802.jpg)

Not so long ago, the average American man in his 20s had achieved most of the milestones of adulthood: a high-school diploma, financial independence, marriage and children. Today, most men in their 20s hang out in a novel sort of limbo, a hybrid state of semi-hormonal adolescence and responsible self-reliance. This “pre-adulthood” has much to recommend it, especially for the college-educated. But it’s time to state what has become obvious to legions of frustrated young women: It doesn’t bring out the best in men.

“We are sick of hooking up with guys,” writes the comedian Julie Klausner, author of a touchingly funny 2010 book, “I Don’t Care About Your Band: What I Learned from Indie Rockers, Trust Funders, Pornographers, Felons, Faux-Sensitive Hipsters and Other Guys I’ve Dated.” What Ms. Klausner means by “guys” is males who are not boys or men but something in between. “Guys talk about ‘Star Wars’ like it’s not a movie made for people half their age; a guy’s idea of a perfect night is a hang around the PlayStation with his bandmates, or a trip to Vegas with his college friends…. They are more like the kids we babysat than the dads who drove us home.” One female reviewer of Ms. Kausner’s book wrote, “I had to stop several times while reading and think: Wait, did I date this same guy?”

For most of us, the cultural habitat of pre-adulthood no longer seems noteworthy. After all, popular culture has been crowded with pre-adults for almost two decades. Hollywood started the affair in the early 1990s with movies like “Singles,” “Reality Bites,” “Single White Female” and “Swingers.” Television soon deepened the relationship, giving us the agreeable company of Monica, Joey, Rachel and Ross; Jerry, Elaine, George and Kramer; Carrie, Miranda, et al.

But for all its familiarity, pre-adulthood represents a momentous sociological development. It’s no exaggeration to say that having large numbers of single young men and women living independently, while also having enough disposable income to avoid ever messing up their kitchens, is something entirely new in human experience. Yes, at other points in Western history young people have waited well into their 20s to marry, and yes, office girls and bachelor lawyers have been working and finding amusement in cities for more than a century. But their numbers and their money supply were always relatively small. Today’s pre-adults are a different matter. They are a major demographic event.

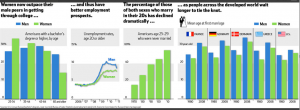

What also makes pre-adulthood something new is its radical reversal of the sexual hierarchy. Among pre-adults, women are the first sex. They graduate from college in greater numbers (among Americans ages 25 to 34, 34% of women now have a bachelor’s degree but just 27% of men), and they have higher GPAs. As most professors tell it, they also have more confidence and drive. These strengths carry women through their 20s, when they are more likely than men to be in grad school and making strides in the workplace. In a number of cities, they are even out-earning their brothers and boyfriends.

There is an old stereotype that men are dogs…apparently not even. But perhaps we just need to to create man years like dog years. If a dog has 7 years for every human year, maybe in accordance with these article, man years would be age divided by 7. Just a thought. What would your equation be?

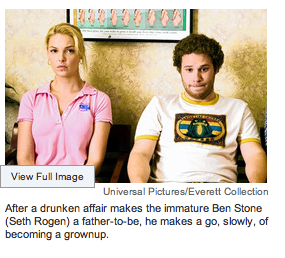

Still, for these women, one key question won’t go away: Where have the good men gone? Their male peers often come across as aging frat boys, maladroit geeks or grubby slackers—a gender gap neatly crystallized by the director Judd Apatow in his hit 2007 movie “Knocked Up.” The story’s hero is 23-year-old Ben Stone (Seth Rogen), who has a drunken fling with Allison Scott (Katherine Heigl) and gets her pregnant. Ben lives in a Los Angeles crash pad with a group of grubby friends who spend their days playing videogames, smoking pot and unsuccessfully planning to launch a porn website. Allison, by contrast, is on her way up as a television reporter and lives in a neatly kept apartment with what appear to be clean sheets and towels. Once she decides to have the baby, she figures out what needs to be done and does it. Ben can only stumble his way toward being a responsible grownup.

So where did these pre-adults come from? You might assume that their appearance is a result of spoiled 24-year-olds trying to prolong the campus drinking and hook-up scene while exploiting the largesse of mom and dad. But the causes run deeper than that. Beginning in the 1980s, the economic advantage of higher education—the “college premium”—began to increase dramatically. Between 1960 and 2000, the percentage of younger adults enrolled in college or graduate school more than doubled. In the “knowledge economy,” good jobs go to those with degrees. And degrees take years.

So where did these pre-adults come from? You might assume that their appearance is a result of spoiled 24-year-olds trying to prolong the campus drinking and hook-up scene while exploiting the largesse of mom and dad. But the causes run deeper than that. Beginning in the 1980s, the economic advantage of higher education—the “college premium”—began to increase dramatically. Between 1960 and 2000, the percentage of younger adults enrolled in college or graduate school more than doubled. In the “knowledge economy,” good jobs go to those with degrees. And degrees take years.

Another factor in the lengthening of the road to adulthood is our increasingly labyrinthine labor market. The past decades’ economic expansion and the digital revolution have transformed the high-end labor market into a fierce competition for the most stimulating, creative and glamorous jobs. Fields that attract ambitious young men and women often require years of moving between school and internships, between internships and jobs, laterally and horizontally between jobs, and between cities in the U.S. and abroad. The knowledge economy gives the educated young an unprecedented opportunity to think about work in personal terms. They are looking not just for jobs but for “careers,” work in which they can exercise their talents and express their deepest passions. They expect their careers to give shape to their identity. For today’s pre-adults, “what you do” is almost synonymous with “who you are,” and starting a family is seldom part of the picture.

Pre-adulthood can be compared to adolescence, an idea invented in the mid-20th century as American teenagers were herded away from the fields and the workplace and into that new institution, the high school. For a long time, the poor and recent immigrants were not part of adolescent life; they went straight to work, since their families couldn’t afford the lost labor and income. But the country had grown rich enough to carve out space and time to create a more highly educated citizenry and work force. Teenagers quickly became a marketing and cultural phenomenon. They also earned their own psychological profile. One of the most influential of the psychologists of adolescence was Erik Erikson, who described the stage as a “moratorium,” a limbo between childhood and adulthood characterized by role confusion, emotional turmoil and identity conflict.

Like adolescents in the 20th century, today’s pre-adults have been wait-listed for adulthood. Marketers and culture creators help to promote pre-adulthood as a lifestyle. And like adolescence, pre-adulthood is a class-based social phenomenon, reserved for the relatively well-to-do. Those who don’t get a four-year college degree are not in a position to compete for the more satisfying jobs of the knowledge economy.

But pre-adults differ in one major respect from adolescents. They write their own biographies, and they do it from scratch. Sociologists use the term “life script” to describe a particular society’s ordering of life’s large events and stages. Though such scripts vary across cultures, the archetypal plot is deeply rooted in our biological nature. The invention of adolescence did not change the large Roman numerals of the American script. Adults continued to be those who took over the primary tasks of the economy and culture. For women, the central task usually involved the day-to-day rearing of the next generation; for men, it involved protecting and providing for their wives and children. If you followed the script, you became an adult, a temporary custodian of the social order until your own old age and demise.

Unlike adolescents, however, pre-adults don’t know what is supposed to come next. For them, marriage and parenthood come in many forms, or can be skipped altogether. In 1970, just 16% of Americans ages 25 to 29 had never been married; today that’s true of an astonishing 55% of the age group. In the U.S., the mean age at first marriage has been climbing toward 30 (a point past which it has already gone in much of Europe). It is no wonder that so many young Americans suffer through a “quarter-life crisis,” a period of depression and worry over their future.

Given the rigors of contemporary career-building, pre-adults who do marry and start families do so later than ever before in human history. Husbands, wives and children are a drag on the footloose life required for the early career track and identity search. Pre-adulthood has also confounded the primordial search for a mate. It has delayed a stable sense of identity, dramatically expanded the pool of possible spouses, mystified courtship routines and helped to throw into doubt the very meaning of marriage. In 1970, to cite just one of many numbers proving the point, nearly seven in 10 25-year-olds were married; by 2000, only one-third had reached that milestone.

American men have been struggling with finding an acceptable adult identity since at least the mid-19th century. We often hear about the miseries of women confined to the domestic sphere once men began to work in offices and factories away from home. But it seems that men didn’t much like the arrangement either. They balked at the stuffy propriety of the bourgeois parlor, as they did later at the banal activities of the suburban living room. They turned to hobbies and adventures, like hunting and fishing. At midcentury, fathers who at first had refused to put down the money to buy those newfangled televisions changed their minds when the networks began broadcasting boxing matches and baseball games. The arrival of Playboy in the 1950s seemed like the ultimate protest against male domestication; think of the refusal implied by the magazine’s title alone.

In his disregard for domestic life, the playboy was prologue for today’s pre-adult male. Unlike the playboy with his jazz and art-filled pad, however, our boy rebel is a creature of the animal house. In the 1990s, Maxim, the rude, lewd and hugely popular “lad” magazine arrived from England. Its philosophy and tone were so juvenile, so entirely undomesticated, that it made Playboy look like Camus.

At the same time, young men were tuning in to cable channels like Comedy Central, the Cartoon Network and Spike, whose shows reflected the adolescent male preferences of its targeted male audiences. They watched movies with overgrown boy actors like Steve Carell, Luke and Owen Wilson, Jim Carrey, Adam Sandler, Will Farrell and Seth Rogen, cheering their awesome car crashes, fart jokes, breast and crotch shots, beer pong competitions and other frat-boy pranks. Americans had always struck foreigners as youthful, even childlike, in their energy and optimism. But this was too much.

What explains this puerile shallowness? I see it as an expression of our cultural uncertainty about the social role of men. It’s been an almost universal rule of civilization that girls became women simply by reaching physical maturity, but boys had to pass a test. They needed to demonstrate courage, physical prowess or mastery of the necessary skills. The goal was to prove their competence as protectors and providers. Today, however, with women moving ahead in our advanced economy, husbands and fathers are now optional, and the qualities of character men once needed to play their roles—fortitude, stoicism, courage, fidelity—are obsolete, even a little embarrassing.

Today’s pre-adult male is like an actor in a drama in which he only knows what he shouldn’t say. He has to compete in a fierce job market, but he can’t act too bossy or self-confident. He should be sensitive but not paternalistic, smart but not cocky. To deepen his predicament, because he is single, his advisers and confidants are generally undomesticated guys just like him.

Single men have never been civilization’s most responsible actors; they continue to be more troubled and less successful than men who deliberately choose to become husbands and fathers. So we can be disgusted if some of them continue to live in rooms decorated with “Star Wars” posters and crushed beer cans and to treat women like disposable estrogen toys, but we shouldn’t be surprised.

Relatively affluent, free of family responsibilities, and entertained by an array of media devoted to his every pleasure, the single young man can live in pig heaven—and often does. Women put up with him for a while, but then in fear and disgust either give up on any idea of a husband and kids or just go to a sperm bank and get the DNA without the troublesome man. But these rational choices on the part of women only serve to legitimize men’s attachment to the sand box. Why should they grow up? No one needs them anyway. There’s nothing they have to do.

They might as well just have another beer.

—Adapted from “Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men Into Boys” by Kay S. Hymowitz, to be published by Basic Books on March 1. Copyright © by Kay S. Hymowitz. Printed by arrangement with Basic Books.

on Twitter

on Facebook

on Google+